🎄👨💻 Day 11: Monkey in the Middle

It wasn’t enough to have risked our lives by falling off a rope bridge into the river flowing in the gorge below. Now we met a group of nasty monkeys who are taunting us by throwing the stuff from our backpack. As we try to figure out how to intervene, we are quite apprehensive about our belongings and assign a certain worry level to each item. The monkeys handle each object a bit and then throw it at each other based on how they see us worrying. Each monkey may show a different interest in our objects, and its actions may increase our worry level a little or a lot.

Part 1

The notes we took on the annoying primate pastime take this form:

Monkey 0:

Starting items: 79, 98

Operation: new = old * 19

Test: divisible by 23

If true: throw to monkey 2

If false: throw to monkey 3

Each monkey examines a single item on her list, plays with it, and this will change the worry level according to the indicated operation. Then, according to the result, the monkey will choose whom to pass it to. Each turn of the game ends when all monkeys have gone through all the items they have. It’s thus possible that one monkey will end up with no items, or that another monkey who had none at the beginning of the turn will end up with some to play with.

At first, we tell ourselves that this is not such a big deal. As long as the monkeys don’t damage our stuff, we manage to keep our worry level under control. Before each monkey passes an object to another, our worry level is divided by a third.

Since it is impossible to focus on all the monkeys, we decide to focus on the two most active ones. We must then determine which of the groups are the most active after 20 rounds. They will be the ones who got their hands on the most objects.

The puzzle has an interesting input and can be approached in several ways. Perhaps complicating my life, I decided that I would use a dictionary – called monkeys – to keep track of each monkey and what items it has on its hands. In addition, the individual blocks of lines that describe a monkey inspired me to use regexes.

import re

def parse(puzzle_input):

"""Parse input"""

monkey_re = re.compile(

r"Monkey (?P<idx>\d+):\n"

r"\s+Starting items: (?P<items>.*?)\n"

r"\s+Operation: new = (?P<op>.*?)\n\s"

r"+Test: divisible by (?P<test>\d+)\n"

r"\s.*true.*?(?P<true>\d+).*?(?P<false>\d+)",

re.MULTILINE | re.DOTALL,

)

monkeys = {}

puzzle_input = puzzle_input.split("\n\n")

for monkey in puzzle_input:

if match := monkey_re.match(monkey.strip()):

props = match.groupdict()

idx = props.pop("idx")

# re-arrange items to be a list of int

props["items"] = list(map(int, props["items"].split(", ")))

# exctract the operation

_op = props.pop("op").split()

if _op[0] == _op[-1]:

op_type = operand = None

else:

operand = _op[2]

op_type = _op[1]

# create a new monkey

monkeys[idx] = props

monkeys[idx]["op"] = partial(op, operand=operand, op_type=op_type)

monkeys[idx]["count"] = 0

return monkeys

The pattern is a bit complicated for those not familiar with regex1. In a nutshell, it uses so-called named groups, so you can extract their corresponding values on the fly as a dictionary (with .groupdict()). The most interesting lines are as follows:

# exctract the operation

_op = props.pop("op").split()

if _op[0] == _op[-1]:

op_type = operand = None

else:

operand = _op[2]

op_type = _op[1]

# ...

monkeys[idx]["op"] = partial(op, operand=operand, op_type=op_type)

partial is a very useful function of the functools module that allows you to specialize more generic functions by fixing some of their parameters. In this case, we create one for each operation: power elevation, sum, or multiplication. The code that defines the generic function is this:

def op(arg, operand=None, op_type=None):

"""Define operation"""

if not operand:

return arg**2

if op_type == "*":

return arg * int(operand)

if op_type == "+":

return arg + int(operand)

return None

At each round of the game, each monkey will inspect and turn over to another all the elements it is holding. To answer Part 1, we need to increment the value of the count2 key, which keeps track of how many items that monkey has seen each round.

def monkey_turn(monkeys, part, divisors):

"""Run a monkey game round"""

for monkey in monkeys.values():

while monkey["items"]:

monkey["count"] += 1

# perform the operation

item = monkey["op"](monkey["items"].pop(0))

if part == 1:

# Part 1

item //= 3

# test and send item

test, true, false = monkey["test"], monkey["true"], monkey["false"]

if item % int(test) == 0:

monkeys[true]["items"].append(item)

else:

monkeys[false]["items"].append(item)

return monkeys

Presumably we will have to simulate the game again in Part 2, so it is worth writing a run_game() function:

def run_game(monkeys, rounds=20, part=1):

"""Run a game"""

counts = []

for _ in range(rounds):

monkeys = monkey_turn(monkeys, part, divisors)

for monkey in monkeys.values():

counts.append(monkey["count"])

a, b = sorted(counts, reverse=True)[:2]

return a * b

Part 2

Here’s where things get funky now. It does not seem the monkeys are going to give up their pastime any soon, and this makes us particularly anxious. This is an excuse to change two things: the values of the worry levels are no longer divided by 3 at each step, and the number of rounds will be much larger, probably 10 000.

And what is the problem with that, we might ask? Aren’t computers extremely fast machines? Sure, but they are not infinite machines, and above all, no machine can ever win against math. If we look at the input, we notice that a monkey performs the following operation: new = old * old. This is a rapidly exploding number, and well before we get to 10 000, it will take a virtually infinite amount of time to square a humongous number.

The solution is to figure out what these numbers are for: we only test their divisibility by certain factors (that they happen to be primes), and the result of the test determines to which monkey an object will be sent. There is a property of modular arithmetic that allows us to avoid the problem of exploding numbers. The property is this: consider a set of prime factors {p1, p2, p3} of which P is the product, and suppose that some number A is not divisible by p1, i.e. A mod p1 != 0. It can be shown3 that (A mod P) mod p1 != 0. And the same relationship applies to all p. The divisibility by any of the individual factors is preserved, we might say.

What we do is to take the result of the operation on each item (worry level) and compute the remainder of the division with the product of P all prime factors that in the puzzle input appear after Test: divisible by.

The code for the second part does not change much. It is only necessary to calculate the product of the factors and replace item //= 3 with item %= P, if we call P the product of the prime factors. The product P can be calculate conveniently with the function prod of the math module:

import math

divisors = math.prod([int(m["test"]) for m in monkeys.values()])

-

You can try it at this website. Copy and paste the pattern and input shown just above. Select “Python” in the “Flavor” menu on the left. ↩︎

-

As we read the input, each monkey is a dictionary to which corresponds a

countkey that is initialized to 0. ↩︎ -

It’s quite straightforward. If

A mod p1 ≠ 0but(A mod P) mod p1 = 0, then it would mean thatA mod P = r = m * p1, wheremis a non-zero integer. In general, we can write an integer likeAask * P + r. If we substituteP = p1 * p2 * p3andr = m * p1, we get thatA = p1 (m + k * p2 * p3), which means thatAis a multiple of the prime factorp1, and that invalidates our hypothesis. ↩︎

🎄👨💻 Day 10: Cathode-Ray Tube

Despite good will and cool heads, our modeling of rope physics didn’t help much. The rope bridge failed to hold, and we fell straight into the river below (there’s a vague Indiana Jones flavor here). We don’t realize in time, and the Elves from on top signal us that they will continue on and to get in touch with them via the device we repaired a few days ago.

Well, not quite. The screen is shattered, and we can only intuit its operation: it’s an old-fashioned CRT display, and maybe we can build one that will bring the device back to life.

Part 1

The device has a 40x6 pixel screen, but first we need to figure out how to handle the CPU. We have a list of instructions (the puzzle input) that shows only two possibilities. The first, a noop, which requires one clock cycle and does, well, nothing. The second addx ARG, which requires 2 clock cycles and, at the end of the second cycle, sums ARG to the current value of an X register, equal to 1 at the beginning of the program. We need to compute a particular value that appears to be associated with the signal sent from the CPU to the monitor. The value of the signal is calculated only at certain checkpoints: every 40 cycles, starting from the 20th, we take the value of the X register and multiply it by the value of the checkpoint.

Implementing the program is quite simple. However, one must pay attention to one detail, which led me down a wrong path and was difficult to debug: the signal is calculated during a given cycle. I calculated it at the end, that is, when an addx instruction had just updated the register. I don’t know if it was a fluke, but with the example input I could still reproduce 5 of the 6 results described in the problem text. It was not trivial to figure out where I was going wrong. I had to check the register values one by one from cycle 180 through 220 to figure out what was going on.

The key piece of the solution for Part 1 is the function that updates the register:

def run(instruction, register, cycle):

"""

Run a given istruction

return the cycles spent in the execution,

and the register value

"""

if instruction == "noop":

cycle += 1

elif instruction.startswith("addx"):

_, arg = instruction.strip().split()

register += int(arg)

cycle += 2

return cycle, register

After realizing my mistake, calculating the value of the signal correctly was a matter of adding a single variable that would save the value in the register before it was updated at the end of the second loop of an addx instruction. The piece of code that runs the program is just a for loop plus an if:

def part1(data):

"""Solve part 1"""

reg = 1

cycle = strength = 0

check = 20

for instruction in data:

last_reg = reg

cycle, reg = run(instruction, reg, cycle)

if cycle >= check:

strength += check * last_reg

check += 40

Part 2

No spoilers, but I have to say right away that the end result of this second part is the most beautiful and fun we have had so far. Check out if you don’t believe me.

Now it is time to connect the CPU and monitor. We are told that the value of the X register indicates the position of a 3-pixel cursor. The monitor is able to render a single pixel at each cycle. A pixel will be turned on if, at a certain cycle, its position is among those occupied by the cursor at that same time. The key point here is that it can take 2 cycles for the cursor position to update, so we need to make sure that the current pixel is always synchronized with the clock cycles.

Since the screen is 40 pixels wide, the index of the current pixel should always be between 0 and 39. We construct the image on the screen as a single array of characters 240 (pixels) long.

# pixel_pos starts at 0

# we also initialized pixels to []

while pixel_pos < cycle:

pixels.append(

"#"

if (pixel_pos % 40) >= last_reg - 1 and (pixel_pos % 40) <= last_reg + 1

else "."

)

pixel_pos += 1

The last step will be to format the array into a 2D image; for this purpose, the partition() function we had written on Day 6 comes to rescue – see how it pays off to be able to write fairly generic code? The final result is obtained in two lines1:

def part2(data):

"""Solve part 2"""

_, pixels = data # result from part1()

screen = partition(pixels, 40) # neat, isn't it?!

return screen

###..#..#..##..#..#.#..#.###..####.#..#.

#..#.#..#.#..#.#.#..#..#.#..#.#....#.#..

#..#.#..#.#..#.##...####.###..###..##...

###..#..#.####.#.#..#..#.#..#.#....#.#..

#.#..#..#.#..#.#.#..#..#.#..#.#....#.#..

#..#..##..#..#.#..#.#..#.###..####.#..#.

The letters that stand out, readable with some difficulty, are RUAKHBEK. This is certainly one of the most beautiful puzzles on the 2022 calendar! Undoubtedly one that deserves some kind of visualization. I will give it a try, I promise, this one will go straight into #to/revisit list.

-

To avoid re-running the entire program, I modified the standard template for the function that solves Part 2 so that it takes as an argument the array of pixels computed in Part 1. Take a look at the complete solution on GitHub. ↩︎

🎄👨💻 Day 9: Rope Bridge

If this Advent of Code 2022 ended tomorrow, I could say with certainty that I have learned at least one fundamental thing: I’m struggling the most when translating a solution that is crystal clear in my head using the “words” of an algorithmic vocabulary. Any one. I read the text, understand the problem, and intuit the solution; for a simple example, I even manage to write it down with pen and paper (when possible). Then I get stuck when I ask myself, “and now how do I tell a computer to follow this reasoning and arrive at the result?”

Today’s puzzle is another Advent of Code classic: you have to navigate a two-dimensional grid of dots by following certain rules. Often the question is to count how many times you pass over a grid point or how many locations have never been visited. The interesting part is how you have to move around the grid.

Today’s back-story was slightly absurd, but only a little. Planck’s length even came up – just because it’s cool to mention it. It is fun to follow the rambling vicissitudes of these Elves, though. After all, it only serves the purpose of introducing the problem.

Part 1

We have a rope with two knots at each end. Each node can move along a grid of points, but obviously both are constrained to follow each other. The two nodes will tend to stay as close as possible. The distances between the two knots apply in all directions, even diagonally. The two ends of the string can also overlap, the most trivial case of adjacency.

The knots can move along the grid according to the following rules:

-

If the head node moves two steps in any direction along the XY Cartesian axes, the tail node will move an equal number of steps in the same direction.

-

If, after a move, the nodes are no longer adjacent and are neither on the same row and column, then the tail node will move diagonally by one step. Keep this rule in mind for Part 2.

Our input is a series of movements. Each line, two columns: the first character indicates the direction, the second the number of steps. We are asked to determine which grid points the tail node visits at least once.

Very schematically, for each move we must:

- Update the position of the leading node.

- Determine where the tail node will end up (it might even stay where it is).

- Add the new location of the tail node somewhere. Eventually, it will suffice to count the elements in this list. Since we are interested in points visited at least once, we must ignore any duplicates. It is possible for a node to pass over a point more than once, if the trajectory described by the input is a bit convoluted.

The most interesting part is step 2: determining how to update the tail coordinates. There are four possibilities:

- The head knot moves along the X axis: the Y coordinate of the tail remains the same, while the X will change by

+1/-1, depending on the direction. - The head moves along the Y axis: as above, but we will update the Y coordinate.

- The head moves diagonally: here we need to update both coordinates, combining what we did for X and Y separately.

There is a really important detail to point out, but first we need the code for this function called move(H, T), with a spark of imagination:

def move(H, T):

"""Adjust position of Tail w.r.t. Head, if need be"""

xh, yh = H

xt, yt = T

dx = abs(xh - xt)

dy = abs(yh - yt)

if dx <= 1 and dy <= 1:

# do nothing

pass

elif dx >= 2 and dy >= 2:

# move both

T = (xh - 1 if xt < xh else xh + 1, yh - 1 if yt < yh else yh + 1)

elif dx >= 2:

# move only x

T = (xh - 1 if xt < xh else xh + 1, yh)

elif dy >= 2:

# move only y

T = (xh, yh - 1 if yt < yh else yh + 1)

return T

Let’s try to understand the last elif dy >= 2 block. If we said that X remains unchanged, why are we substituting the X coordinate xh of the head node? Because the two nodes can also be diagonally adjacent; in this case, the tail node will have to make a diagonal jump. Here’s a ridiculously simple example to clarify:

(a) (b)

...... ......

...... ....H.

....H. ....*.

...T.. ...T..

When H moves from (4, 1) in (a) to (4, 2) in (b), T will have to move to the point indicated by *. The coordinates of T are (3, 0), and the distances are dx = 1 and dx = 2. If we left the X of T unchanged, it would not move at all along X! This is why we substitute the X of H. In the trivial case where H was moving up and T was exactly below, it would be irrelevant which X coordinate we keep.

The gist of the first part is all here. The rest of the code to get the solution is

Where the two dictionaries delta_x and delta_y simplify a lot the update of the coordinates of H, which can be done in a single, neat line.

delta_x = {"L": 1, "R": -1, "U": 0, "D": 0}

delta_y = {"L": 0, "R": 0, "U": 1, "D": -1}

def part1(data):

H = (0, 0)

T = (0, 0)

tail_path = set([T])

for direction, step in data:

for _ in range(int(step)):

# Update the head's position

H = H[0] + delta_x[direction], H[1] + delta_y[direction]

# Update the tail's position

T = move(H, T)

tail_path.add(T)

return len(tail_path)

Part 2

Only two knots?! What is this trivial and boring stuff? Why don’t we use a rope of 10 knots! Sure, no problem, because we just need to update all nodes in pairs according to the same rules.

I must admit that my first implementation did not use the above function move(), but a more trivial one that simply determined whether node T should move or not. If yes, the position of T would be updated to the penultimate position of H.

Unfortunately, this method does not work with more than two nodes: there are multiple ways to move a node that bring it back adjacent to its nearest companion. The correct one is only the one that keeps the two nodes at the minimum distance. Another trivial example:

(a) (b)

...... ......

...... ....H.

....H. ...*1.

4321.. 432*..

The node 2 could move to either position indicated by * because both satisfy the adjacency criterion. But only one of them is at the minimum distance, namely the one immediately to the left of 1. By the same reasoning, also the other nodes should move up, and not to the left. It was the tricky detail of Part 2, but the function move() is general enough to deal with this scenario.

The code to solve Part 2 is only a tiny bit more complicated than Part 1: we basically have to add an extra for loop:

def part2(data):

H = (0, 0)

T = [(0, 0) for _ in range(9)]

tail_path = set([T[-1]])

for direction, step in data:

for _ in range(int(step)):

# Update the head's position

H = H[0] + delta_x[direction], H[1] + delta_y[direction]

# Update the first point that follows the head

T[0] = move(H, T[0])

# Update the remaining points

for i in range(1, 9):

T[i] = move(T[i - 1], T[i])

# Add the tail's position to the path

tail_path.add(T[-1])

return len(tail_path)

After reading the puzzle’s text, I wanted to come up with some nice visualization of the strand moving on the grid, but I don’t have (yet) a clue on how to do that. I’ll collect all the puzzles where it could be fun to add some graphics and see to which one I can come back later. Now, I’ll pat on my shoulder for Day 9’s two stars! ⭐⭐

🎄👨💻 Day 8: Treetop Tree House

Eric keeps raising the bar with a problem that made me disown Python because otherwise I would have took much longer. I started sketching the solution with the Wolfram Language and wanted to finish the whole puzzle. I will try to recount the highlights of the code that, by the way, earned me today’s stars.

Part 1

The Elves’ project is to build a cozy treetop house. It is not clear how much time they have for this expedition, but so be it. The vast forest in which they find themselves covers a fairly regular area, and the Elves are able to reconstruct a two-dimensional map of it in which each tree is represented by its height1, from 0, the lowest height they have been able to measure, to 9.

The Elves first want to determine where it would be ideal to build the tree house. They need to find the most hidden location possible. They ask us to determine how many trees are visible to an observer outside the forest. A tree is visible if all other trees between it and the forest boundaries are shorter than it. It’s clear that all trees at the edges of the forest will always be visible, so we can already discard them as possible candidates (but we will come back to this in Part 2).

Reading the input is rather simple today: it’s a list of strings with integer digits from 0 to 9. We need to read it in as a matrix of integers:

Map[FromDigits, Characters /@ StringSplit["input.txt", "\n"], {2}]

Given a grid point, we must consider the points to the right, left, top, and bottom, and determine which trees are lowest. A tree will be visible if at least one of these “forest segments” contains only lower trees in height.

For each point (i, j), the row and column containing it will be row = forest[i][:] and col = forest[:][j]2.

From row and col we need to extract two sets of points: those to the right/left and above/below the point under consideration, excluding the point itself. The Wolfram Language has a dedicated function: TakeDrop[list, n] returns two lists, one containing the first n elements, and the second those remaining.

Here is the first piece of the function for the first part ((x, y) are the coordinates of the point):

With[{row = matrix[[x, ;;]], col = matrix[[;; , y]]},

{sx, dx} = TakeDrop[row, y];

{up, do} = TakeDrop[col, x];

]

The procedure for looking for visible trees could be put into words like this: look along the row, right then left, and check for all lower trees. Repeat along the column, up then down. The important logic is as follows: in the right/left (or top/bottom) direction, all trees must be lower than the one we’re considering. But only one part of a row/column must meet the criterion for the tree to be visible.

Here is the complete function that, given a point p, its coordinates, and the matrix-forest, tells us (True/False) whether the tree is visible:

VisibleQ[p_, {x_, y_}, matrix_] :=

Block[{sx, dx, up, do},

With[{row = matrix[[x, ;;]], col = matrix[[;; , y]]},

{sx, dx} = TakeDrop[row, y];

{up, do} = TakeDrop[col, x];

AllTrue[Most@sx, p > # &] ||

AllTrue[dx, p > # &] ||

AllTrue[Most@up, p > # &] ||

AllTrue[do, p > # &]

]

]

We just need to apply it to every point in the matrix-forest. Here we have to pull another gem out of Wolfram’s hat: MapIndexed. It does the same thing as Python map(), but it also passes the indices of the current list item to the function to be mapped. A trivial example:

MapIndexed[f, {a, b, c, d}]

(* {f[a, {1}], f[b, {2}], f[c, {3}], f[d, {4}]} *)

And it works with objects of any size! We just need to specify at what level we want to apply the function.

Count[

MapIndexed[VisibleQ[#1, #2, forest] &, forest, {2}],

True, {2}

]

Part 2

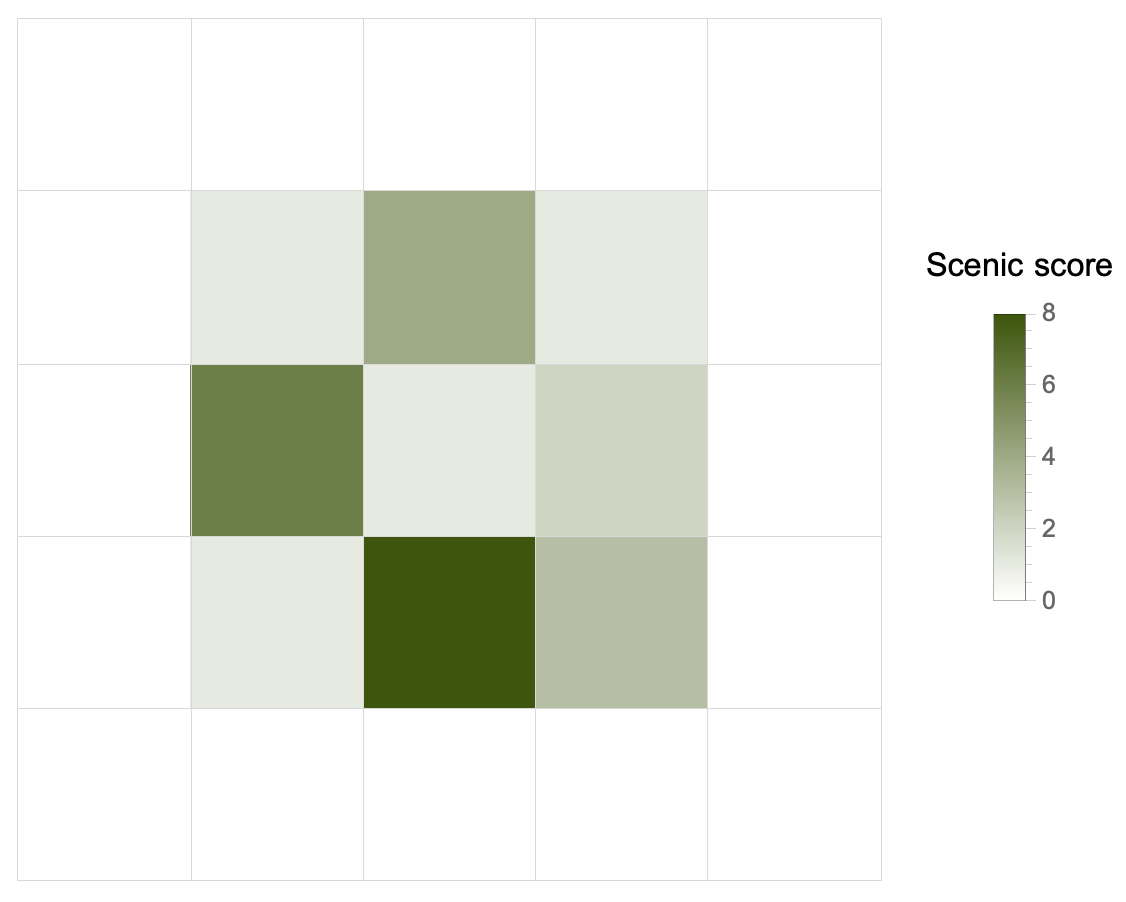

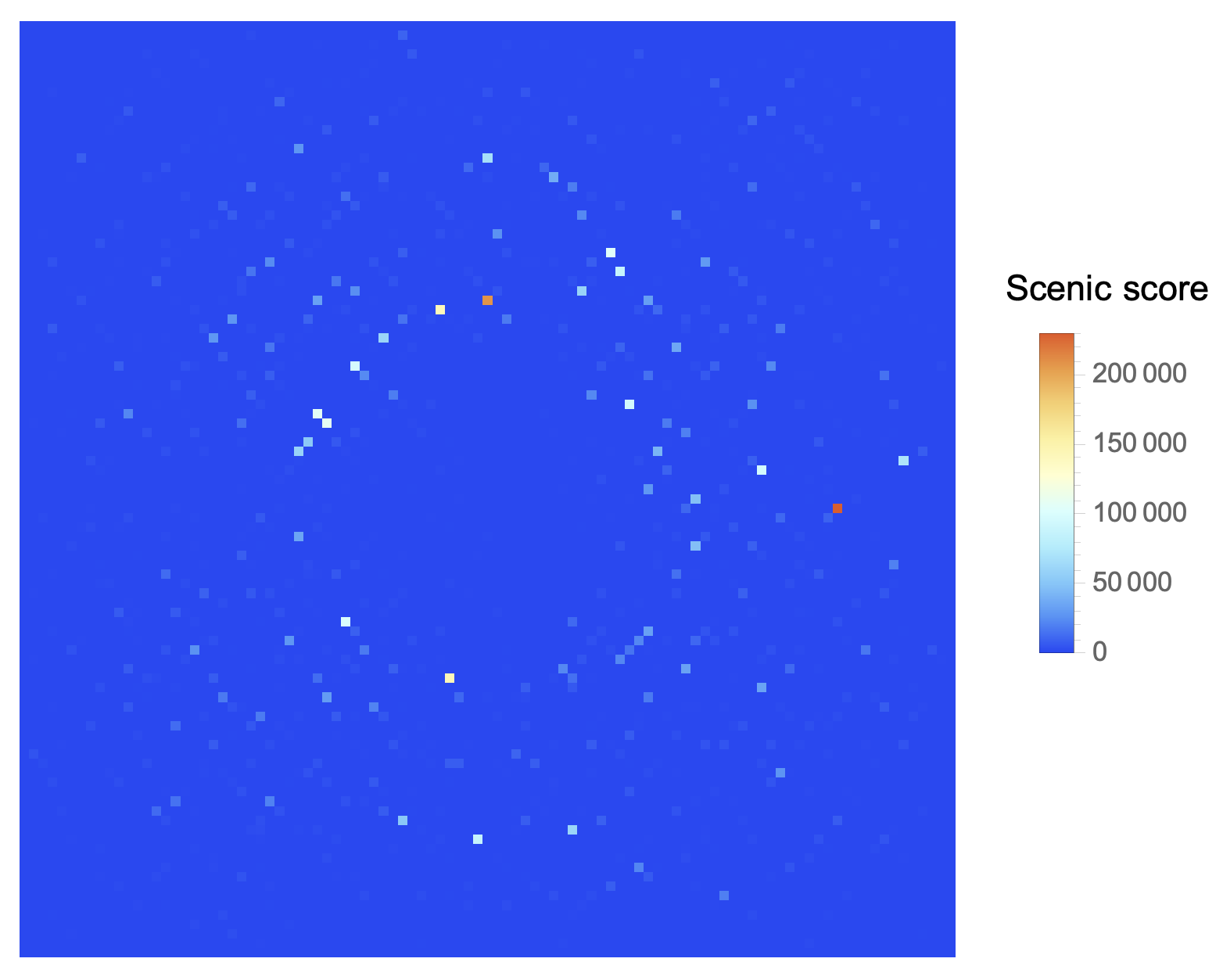

Now things definitely get more complicated, because we have to find the best tree. How? According to a scenic score which is the product of four numbers, one for each side. Each number is the maximum distance along which we can admire the view without being blocked by taller trees.

We must have a function that, given a point (tree) and a list (its row/column “neighbors”), calculates the 4 distances. It increments a counter variable for each lower tree. As soon as it encounters an equal or taller tree, it stops and returns the counter, which will be the distance searched.

counter[value_][list_] :=

Catch[

list === {} && Throw[0];

Block[{total = 0},

Scan[Which[# < value, ++total, # > value || # == value,

Throw[++total]] &, list];

Throw[total]

]

]

Now we have two steps to get to the solution.

(1) For each point, we find once again the 4 lists of neighboring points (left/right, up/down):

Flatten[MapIndexed[pick[#2, forest] &, forest, {2}], 1]

pick is the middle portion of the VisibleQ function seen in Part 1. I have made it self-contained for simplicity. For instance, for the point (1, 1) of the example input, this function spits out something like: {3, {{}, {0, 3, 7, 3}, {}, {2, 6, 3, 3}}. The point (1, 1) corresponds to the height value 3 and:

- on the left, it has no neighbors (it’s on the left border);

- on the right, it has

{0, 3, 7, 3}, in that exact order; - it has no neighbors above (so it’s in the upper right corner);

- it has

{2, 6, 3, 3}below.

(2) To apply the counter function3 we need a double Map: the first will scroll over lists like {p, {sx, dx, up, down}}. The second will apply counter` to each neighbor list, keeping the reference point fixed. It will come up with another list that will again be a matrix: each point-tree will be associated with the four distances, which, multiplied, will give the scenic score.

All that remains is to find the maximum of this list as a function of the product of the 4 distances. This is easy thanks to MaximalBy:

MaximalBy[

Map[Map[counter[#[[1]]], #[[2]]] &,

Flatten[MapIndexed[pick[#2, data] &, data, {2}], 1]],

Apply[Times]

] // Flatten /* Apply[Times]

The last bit, Flatten /* Apply[Times], is just multiplying the resulting 4 values to obtain the scenic score.

😓 It is 23:38 and I have not yet had my evening herbal tea. I’m really starting to believe that I don’t think I will endure until Christmas with this frantic pace of finding the solution and writing the report. I’m going to try, though, as long as I keep up.

Bonus: maps

-

A perfect representation of a field in physics. Inevitable note because the writer is proud of his scientific background, although he likes a lot computer science stuff. ↩︎

-

This is not the right way to slice a 2D list in Python; it’s pseudo-code to give an idea. ↩︎

-

Or at least in the way I wrote it. I thought of simplifying it to allow a clearer application, but I didn’t have time today. I’m sure I’ll go through these notes once again in the future, also because I want to write a Python solution as well. ↩︎

🎄👨💻 Day 7: No Space Left On Device

The dreaded day came, eventually. Without a little hint, I would not have been able to pull out the solution.

The problem was not that I didn’t have a clue on how to solve the puzzle, but that I was stuck with my first approach, refusing to change perspective. That is why the account of this seventh calendar day is perhaps the most important of all the previous ones. Because I found a difficulty that, at first, had completely blocked me. Then a change of point of view allowed me to find the correct solution.

Today’s problem, in short. The Elves’ apparatus has more than its messaging system malfunctioning. You attempt to execute a system update, but it does not go through since there is insufficient disk space available. You inspect the filesystem to examine what’s happening and record the terminal output generated.

The output is very similar to what you would get on a UNIX system. The cd and ls commands are used to change and list the contents of a directory. Each file is associated with its size in bytes (?).

Part 1

Since we have to try to free up space, the first thing to do is to calculate the size of each directory. One directory can contain others, and we have to take this into account to calculate the final size.

My initial idea was to build a data structure that was as similar as possible to the filesystem nested hierarchy. Each entity in this collection of elements had to contain, eventually, other entities (if it were a directory), or simply the name of the file and its size.

I therefore wrote this class:

class Dir:

"""A Dir class"""

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.children = {}

self.parent = None

self.size = 0

def add(self, child, value=None):

"""Add children to Dir"""

self.children[child] = value

def total(self):

"""Total size of this Dir"""

if self.children:

for child in self.children.values():

self.size += child.total() if isinstance(child, Dir) else child

return self.size

def __repr__(self):

return f"Dir({self.children}, parent: '{self.parent.name if self.parent else None}')"

The .total() method already does what one would expect: calculate the total of a directory, following recursively any nested directory. The real stumbling block I haven’t yet overcome was figuring out how to calculate the size of individual directories. Why? Because the puzzle clearly says that, for example, a baz.txt file in the /foo/bar/ directory will contribute to the size of both directories plus the root /. I swear I was unable to write the code that would allow me to do this simple operation.

I was taking too long, so I took a detour on YouTube and was inspired by a video by Jonathan Paulson, a competitive programmer who almost always manages to be in the top 100 people who solve both Advent of Code puzzles. I only had to listen to how he described the problem to figure out how to rewrite the solution. The idea was very simple: simply keep track of each path and its size in a trivial dictionary and without creating a nested object.

Here’s my second attempt with the parsing function:

from collections import defaultdict

def parse(puzzle_input):

paths = []

sizes = defaultdict(int)

for line in puzzle_input.splitlines():

words = line.strip().split()

if words[1] == "cd":

if words[2] == "..":

paths.pop()

else:

paths.append(words[2])

elif words[1] == "ls" or words[0] == "dir":

continue

else:

size = int(words[0])

for i in range(1, len(paths) + 1):

sizes["/".join(paths[:i])] += size

return sizes

For each line in the input, there are three action we can take:

- Change directory, either down or up. If down, record append the new path to the list of paths. If up, remove the last added path (with our friend

.pop()) - List the content of the directory. We simply ignore this line.

- Read a directory’s content. If a line starts with

dir, it indicates that the current file a directory, so we ignore it: we’re gonna explore that directory later on. If it starts with an integer, we save it.

The following bit of code it’s the interesting one. It’s where we add the size of the current file to all directories it belongs to. That is, to all of its parents up to /. We perform a loop over the parents paths, we build a nice UNIX-like path string, and then add the file size.

size = int(words[0])

for i in range(1, len(paths) + 1):

sizes["/".join(paths[:i])] += size

Part 1 asks us to find all the directories that are at most 100 000 in size. That’s pretty easy with our sizes dictionary:

def part1(data):

total = 0

for size in data.values():

if size <= 100_000:

total += size

return total

Part 2

The second part asks us to find the smallest directory that would allow running the upgrade. We know the total space available and the space required by the update. Thus:

avail = 70_000_000

needed = 30_000_000

max_used = avail - needed

free = data["/"] - max_used

The max_used is the maximum space we are allowed to use. The minimum space we need to free up is the total space we’re occupying, data['/'] – the space of the root directory – minus the allowed maximum. It means two operations: a filtering and then sorting.

def part2(data):

avail = 70_000_000

needed = 30_000_000

max_used = avail - needed

free = data["/"] - max_used

candidates = list(filter(lambda s: s >= free, data.values()))

return sorted(candidates)[0]

Day 7 is done, but I have to thank Jonathan Paulson because, without his hint, I doubt I would have been able to finish today. But that’s what happen when you’re trying to learn, right? You push yourself until it’s not longer easy and you’re stuck with a seemingly insurmountable difficulty. Then, with the help of someone more experienced or by studying the subject a little more, one is often able to overcome the stumbling block. And it is this experience that, as it accumulates, makes all the difference in the world in any learning process.

“Hey, Edoardo, do you have also a nice and elegant solution in the Wolfram Language?”

“Next time, my friend. Perhaps as a Christmas present. Now I’m pretty satisfied with what I got.”

🎄👨💻 Day 6: Tuning Trouble

The preparation phase is finally over, and the expedition in the jungle can begin. You and the Elves set off on foot, each with their backpack filled only with what you’ll need (hopefully). Suddenly, one of the Elves hands you a device. “It has fancy features,” he says, “but you need to set up its communication system right away.” He adds with a grin, ”I heard you know your way around signal-based systems - so this one should be easy for you!” They gave you an old, malfunctioning device that you need to fix. ‘Thanks a lot, friends!’

No sooner had he finished speaking, some sparks signals that the device is partially working! You realize it needs to lock onto their signal. To make it work as it should, you must create a subroutine that detects when four unique characters appear in sequence; this indicates the start of a packet in the communication data-stream.

Your task is clear: given an input buffer, find and report how many characters there are from its beginning to the end of that four-character marker.

Part 1

If we can scan the input and split it in overlapping subsequences of 4 chars, then we could compare them and find the first one that doesn’t contain duplicates characters. That one would be our marker string.

We need to have a utility function for that purpose. It should behave as if a four-characters wide windows scrolled over the string. The offset between one substring and the next is exactly one character. We also need to consider that we might end up with strings that are shorter than the target length if there are not enough characters left.

Here’s our partition() function:

def partition(l, n, d=None, upto=True):

"""

Generate sublists of `l`

with length up to `n` and offset `d`

"""

offset = d or n

return [

lx for i in range(0, len(l), offset)

if upto or len(lx := l[i : i + n]) == n

]

To obtain the solution, we need to transform each sublist into a set to remove any duplicates. Only the resulting sets whose length is still 4 characters are potential candidates for our marker string. We can filter out the others and take the first one. Then, find the index in the original string where our substring starts. Python has the str.find(substr) method for that precise purpose.

def part1(data):

pdata = list(map(set, partition(data, n=4, d=1, upto=False)))

marker = list(filter(lambda x: len(x) == 4, pdata))[0]

return ("".join(data)).find("".join(marker)) + 4

Why are we summing 4 at the end? Because the puzzle asks for “the number of characters from the beginning of the buffer to the end of the first such four-character marker.”

Part 2

There’s a slight plot twist: we also need to decode the start of messages with another, appropriate marker. This time, the marker string is 14 characters long. Once again, our partition() function is versatile enough: we only need to change the offset argument to 14. The code is identical to Part 1’s.

My source of inspiration

As I was able to find the complete solution in a short time, I took some time to make some comparisons with another programming language. A particularly special language since it was the first one I learned: the Wolfram Language (now “WL” for short). For this kind of tasks, it really excels, I have to say. The idea of implementing the partition() function came from remembering that WL has an identical function with many, many more options.

The elegance of the solution written in WL is astonishing (but, as I said, I’m completely biased). I let the reader judge by themselves.

With[{sample = inputDay6},

Flatten/*Last@

StringPosition[sample,

StringJoin@Select[

Partition[Characters@sample, 4, 1],

DuplicateFreeQ, 1]

]

]

🎄👨💻 Day 5: Supply Stacks

It’s starting to get serious today, at least as far as input parsing is concerned. The Elves are still in the process of unloading the materials needed for the expedition. On the cargo ship, the material is arranged in crates stacked in a certain order. It would be too easy (and unrealistic) if we could unload all the crates. The ones we need are scattered on the ship, piled in different groups.

The ship’s operator is quick to determining in what order to move the crates so as to retrieve those that the Elves need. They, however, forgetful as they are, do not remember which crates will be the ones they can unload first, that is, the ones that will be at the top of each stack at the end of the “sorting” procedure.

Part 1

The input is divided into two parts. The first, the different stacks with crates before the intervention of the operator. The second, the list of rearrangement operations. It is the first part that is problematic. The example input reads

[D]

[N] [C]

[Z] [M] [P]

1 2 3

If the operator were to move 2 crates from the second to the third stack, for example, she will move one at a time. Which means that the order of the crates will be reversed: the first crate moved will end up as far back as possible in the stack to which it is moved.

In order to handle crate stacks as if they were lists, we need to find a way to convert a list like [[D], [N,C], [Z,M,P]] to [[Z,N], [M,C,D], [P]]. Unfortunately, this is not a simple transposition, but two operations are needed:

-

Reverse the matrix, that is, read it row-by-row from the bottom

-

Now transpose the matrix

For the two steps to work, one more thing is necessary: you must keep the blanks. For example, the first line cannot be [ [D] ], but must be [ [blank, D, blank] ].

There is another problem to handle in parsing the input if we want the transpose operation to make sense: the array must be square, or at least rectangular.

The steps to parse the input are the following:

-

Split the stacks initial configuration from the rearrangement procedure (easy: it’s just a double

\n\n) -

Save how many columns we have, that’s important. It can be done by counting the number of digits at the very bottom of the stacks configuration

-

Read the list of moves. I used the regular expression

r"move (\d+) from (\d) to (\d)"to read in a tuple like(num, src, dest):numis how many crates are moved,srcfrom which stack anddestto which one

And now, the fun part. To process the stacks configuration and obtain our matrix, we need to:

-

Read each line of the stacks section and strip any non-letter character. We also replace any empty “slot” with a dot (

.) placeholder, needed to have a square, transposable matrix -

If the number of

rowsis less than the number ofcols, we need to add extra rows (filled with dots). Again, that’s to obtain a square matrix. How many rows? Enough to haverows == cols, that is,["." * cols] * (cols - rows) -

Now we can transform our matrix. We reverse it first, and then transpose rows and columns

-

Last step: we get rid of all the dot placeholders, which represent non-existent crates (or empty ones, if you want). This can be done with

filter(lambda x: x != ".", stack)

I’m 99% sure that’s not the easiest or clearest way, but I had so much fun in trying to implement this matrix approach1. The problem resembles a lot the Hanoi Towers’ puzzle, and I bet there are hundreds of schemes or algorithms to solve it.

To obtain the answer to Part 1, we only need to process our stacks according to the list of moves. Remember: we must move the crates one by one. That’s easy enough now that we have our matrix of stacks:

def part1(data):

stacks, moves = data

for num, src, dest in moves:

s, d, n = int(src) - 1, int(dest) - 1, int(num)

for _ in range(n):

stacks[d].append(stacks[s].pop())

return "".join(map(lambda x: x[-1], stacks))

We also need to decrement all the indexes in each move because Python counts from zero. The return statement simply takes the topmost crate in each stack and then joins the characters to get the final answer 🎉.

Part 2

It has to be expected: it turns out that the “giant cargo crane” can move more than one crate at a time. Even better: as many as we want. The code change is minimal because the bulk of the work was reading and saving the crates stack in the right way.

The only thing that changes is that we don’t need the loop for _ in range(n) because we can move more than one crate at a time. We also cannot use pop() because it does not support a range, so we have to do it by hand: extract the elements we are interested in and then delete them.

def part2(data):

stacks, moves = data

for num, src, dest in moves:

s, d, n = int(src) - 1, int(dest) - 1, int(num)

stacks[d].extend(stacks[s][-n:])

del stacks[s][-n:]

return "".join(map(lambda x: x[-1], stacks))

It's 11:59 pm, and Day 5 is finally over. Unexpectedly tough.

🎄👨💻 Day 4: Camp Cleanup

Today the Elves start working for real: they need to clear the base camp to make enough space to unload the rest of the material for the upcoming expedition.

“Let’s divide the whole area to clear,” an Elf suggests.

“Good idea, let me take care of it,” another one replies.

So the enthusiastic Elf divides the sections and assigns them to the other Elves who will work in pairs. Each pair will work on two ranges of sections, for example 2,4-6,8: the first Elf will handle sections 2 to 4, the second from 6 to 8.

Unfortunately, the enthusiastic Elf made a bit of a mess. He didn’t realize he assigned overlapping ranges. So we have to find out how many sections are already contained in others, so that we can reassign them and avoid unnecessary work for the Elves.

Part 1

As on Day 3, the anatomy of the problem suggests using sets. We need to determine if a group of numbers is a subset of another or which numbers two groups have in common. Both of these operations are immediate with a set.

Perhaps the most interesting part of today’s puzzle is how to parse the input. We have:

2-4,6-8

2-3,4-5

5-7,7-9

...

and we want

[

[[2,4], [6,8]],

[[2,3], [4,5]],

[[5,7], [7,9]],

...

]

We can do the first step of input parsing in one line (because it’s fun):

data = [

list(map(lambda p: list(map(int, p.split("-"))), pair.split(",")))

for pair in puzzle_input.splitlines()

]

- We split each line at

, - Each of the elements of this list is split again at

-, and then each element is converted to integer withmapand thelambdafunction.

The second step of the parsing phase is to build a “list of pairs of sets”, where each element of the pair includes all the IDs in the range. Here we need to consider one important detail: the ranges must include the last ID. Hence, we must increment by 1 the second element of each range, otherwise Python will ignore it. That’s a for loop and another map:

sets = []

for p1, p2 in data:

# range must be inclusive

p1[1] += 1

p2[1] += 1

p1, p2 = map(lambda x: set(range(*x)), (p1, p2))

sets.append((p1, p2))

Once we did that, the solution to Part 1 is almost immediate: we only need to find if, in each pair, any set is a subset of the other, and count how many of these overlapping sets there are:

def part1(data):

overlaps = 0

for p1, p2 in data:

if p1 <= p2 or p1 >= p2:

overlaps += 1

return overlaps

Part 2

The second part of the problem asks us to find (and count) those pairs of ID ranges that overlap for at least one ID. The total will necessarily be greater than the number found in Part 1. The way we read the input allows us to find the solution by changing only one line from Part 1:

def part2(data):

overlaps = 0

for p1, p2 in data:

if p1 & p2:

overlaps += 1

return overlaps

🎄👨💻 Day 3: Rucksack Reorganization

It’s a classic problem of those who are not used to hiking: preparing a backpack and carrying only what is necessary, no extra unneeded stuff.

The Elves made a big mess with the backpacks. Each backpack has two equal compartments, and there is a finite list of items that they can bring with them. Our input is the list of contents of the backpacks. Each line is a string in which each character represents an item class. Some people put more stuff and some put less, but the two compartments contain the same number of items. The problem is that the person who made the backpacks put some items of the same type in both compartments. That’s unnecessary weight.

Part 1

Not all elements have equal priority, and we have to calculate the total priority of those elements that are present in both compartments. We know that there is only one class of items.

The priorities are calculated simply according to alphabetical order. Elements labeled a-z have priorities 1-26, while those A-Z will have 27-52. We can construct a dictionary on the fly that contains each element with its priority:

# a-z and A-Z letters

from string import ascii_lowercase, ascii_uppercase

prios = {letter: prio for prio, letter in \

enumerate(ascii_lowercase + ascii_uppercase, start=1)}

The gist of the problem is an intersection operation between the two compartments of each backpack. And again, everything is already built-in into Python thanks to sets1. Thus:

- We divide the string of each row in two and construct two sets.

- We do the intersection and then retrieve the priority of the common element.

Part one’s solution is the sum of all priorities:

def part1(data):

"""Solve part 1"""

total = 0

for line in data:

mid = len(line) / 2

first, second = set(line[:mid]), set(line[mid:])

total += prio[(first & second).pop()]

return total

Using .pop() seems to be naive as the resulting set will have only one element, but a standard set doesn’t support indexing2.

Part 2

We know that the Elves will take part in the expedition in groups of three. Each group splits the load into the three backpacks, but there is one item that each Elf must always have: their badge. Each trio will have a badge indicated with a different letter, but we do not know which letter each group’s badge corresponds to.

Since each Elf has only one badge, we need to find which item’s class is present in all their backpacks. Instead of the compartments of a single backpack, we must consider the entire contents of the three backpacks in the group:

def part2(data):

"""Solve part 2"""

total = 0

i = 0

for line in data[::3]: # we jump by 3 lines

group = set(line) & set(data[i+1]) & set(data[i+2])

total += prio[group.pop()] # same thing as in Part 1

i += 3 # don't forget to increase the counter!

return total

I suspect that the for loop with the manual counter isn’t the best way to implement that logic, but I didn’t come up with a better solution (for the moment).

🎄👨💻 Day 2: Rock Paper Scissors

Second day, second warm-up.

The Elves are setting up base camp before venturing into the jungle. To decide who will get the best-positioned tent – that is, the one closest to the food supply meticulously calculated yesterday – the Elves are holding a Rock-Paper-Scissors tournament. The rules are the standard ones, but the scoring will be done as follows:

- 1, 2, and 3 points are awarded to rock (indicated by A), paper (B), scissors (C), respectively;

- Outcome points: 6 points for a win, 3 for a tie, and zero otherwise.

The input is the secret key provided to us by a friendly Elf so that we can easily win the tournament. There’s not much structure and it’s quite easy to parse, only a bunch of rows with two letters.

Part 1

The problem is on the interpretation of the input: we do not know what the second column indicates, where X, Y, and Z stand for rock, paper, and scissors.

We make an hypothesis: if the second column represents our choice during a single match, then we need only add the value associated with the character (A=1, B=2, C=3) in the second column to that of the outcome of the game.

def part1(data):

"""Solve part 1"""

POINTS = {"X": 1, "Y": 2, "Z": 3}

total_points = 0

for line in data:

opp, me = line.split()

total_points += POINTS[me]

if opp == "A":

if me == "X":

total_points += 3

elif me == "Y":

total_points += 6

elif opp == "B":

if me == "Y":

total_points += 3

elif me == "Z":

total_points += 6

else:

if me == "Z":

total_points += 3

elif me == "X":

total_points += 6

return total_points

Part 2

There’s a second possibility, which turns out to be the correct one: the second column means the outcome that the game needs to have. In fact, it would be very suspicious if we won every game; someone would suspect that we are cheating (as we are).

In this case, we already know the score of the final outcome – that’s the score associated to X (0, lose), Y (3, draw), and Z (6, win). We have to find which choice between rock-paper-scissors will produce that outcome. The first column always represents our opponent’s choice.

We only need a couple more if...else, but the solution is fairly easy:

def part2(data):

"""

Solve part 2

X = lose

Y = draw

Z = win

"""

ENDS = {"X": 0, "Y": 3, "Z": 6}

total_points = 0

for line in data:

opp, end = line.split()

total_points += ENDS[end]

# lose

if end == "X":

if opp == "A": # rock

total_points += 3

elif opp == "B": # paper

total_points += 1

else:

total_points += 2

# draw

elif end == "Y":

if opp == "A": # rock

total_points += 1

elif opp == "B": # paper

total_points += 2

else:

total_points += 3

# win

else:

if opp == "A": # rock

total_points += 2

elif opp == "B": # paper

total_points += 3

else:

total_points += 1

return total_points

A very elegant solution (not mine)

One could say very Pythonic. It takes full advantage of the versatility of dictionaries1 and the sum operation between two strings which means to concatenate.

First, we create a dictionary that stores the values of the single choices (A=X=1, B=Y=2, C=Z=3) and the 9 possible outcomes (AX, AY, AZ, etc…).

points = dict(X=1, Y=2, Z=3,

AX=3, AY=6, AZ=0,

BX=0, BY=3, BZ=6,

CX=6, CY=0, CZ=3)

The first part is practically solved in one line, without even an if...else block:

total_points = sum(points[me] + points[me + opp]

for opp, me in [line.split()

for line in open('input.txt').readlines()])

Wow 🤯.

-

Review: a built-in data-structure of key-value pairs ↩︎

🎄👨💻 Day 1: Calorie Counting

The first day - maybe the first week - is just warming up. It serves to get us back into the mood, a Christmas-flavored atmosphere that is anything but passive: it is not the awaiting of something or someone that is supposed to come, but a road that will get steeper day by day to make us sweat out the 25 stars before Christmas.

In this year’s adventure, the Elves are on an expedition to a mysterious island to retrieve Santa’s reindeers favorite food, food that contains the indispensable “magic energy”. There will be a jungle to traverse, so let’s get ready for some obstacle running or mazes among the trees.

Part 1

The Elves sort the food they brought with them and want to make sure they have enough. We need to count how much food each Elf brings. The puzzle input divides each Elf’s rations into blocks separated by blank lines. So here’s how to read the input: divide it at the blank lines and convert everything to integers.

lines = [

list(map(int, line.strip().split("\n")))

for line in re.split(r"^$", puzzle_input, flags=re.M)

]

We’ll end up with a list of lists. To find the solution, it suffices to sum up each sub-list, and then find the largest sum of all.

A quick explanatory note: we used the re.split() method (from the re standard library package) to be able to split the input at every empty line, represented by the regex ^$. The flag re.M (which is a shortcut to re.MULTILINE) is important to match each empty line. Otherwise ^$ would match the start/end of the whole string only.

sums = sorted([sum(l) for l in lines], reverse=True)

print(sums[0]) # the largest sum

Part 2

The Elves want to know the three in the group who have the most food, to make sure that no one will run out of food during the expedition. The solution is straightforward: all we have to do is pull out the first three items from the list of sums obtained in Part 1 (i.e., the top three), and then add up these three numbers. It’s as easy as

print(sum(sums[:3]))

E adesso?

Era ciò che li aveva spinti a lottare per il loro sogno, ed era ciò che faceva andare avanti me, e altre centinaia di escursionisti su lunga distanza, nei giorni più duri. Non aveva nulla a che fare con l’attrezzatura né con le calzature o la moda del trekking, niente a che vedere con filosofie di un’epoca particolare e neppure con il fatto di andare dal punto A al punto B. Aveva a che fare soltanto con la sensazione che ti dava stare nella natura. Con ciò che significava camminare per chilometri senza altra ragione se non vedere il succedersi di alberi e prati, montagne e deserti, torrenti e rocce, fiumi ed erba, albe e tramonti. Era un’esperienza potente e fondamentale.

—Cheryl Strayed, “Wild”

7 giorni di cammino, più di 120 chilometri percorsi (includendo le due vette, Cima d’Asta e Monte Mulaz), 7300 metri di dislivello positivo e 6500 metri di dislivello negativo. Potrei aggiungere i dati delle calorie bruciate, del numero di passi, o qualsiasi altra metrica, ma nessun numero renderebbe l’idea dell’esperienza “potente e fondamentale” che è stata questa traversata trentina, dalla Val di Fiemme alla Val Cordevole sul Sentiero Italia CAI.

Il blog che abbiamo aggiornato qui (quasi) quotidianamente ha provato a raccogliere sensazioni, pensieri, e alcune foto durante il trekking; abbiamo dovuto aspettare qualche giorno dopo averlo concluso per poter maturare dei pensieri a riposo. Frequento la montagna da anni e l’ho fatto in molti modi diversi, ma l’esperienza del trekking su lunga distanza per me è diventata la scelta prediletta per esplorarla, anzi, per conoscerla davvero. Anzitutto, c’è il tempo trascorso in ambiente, a volte assai variegato come su questo tratto del Sentiero Italia. Si parla di acclimatarsi solo quando si sale in verticale, soprattutto quando la meta è una vetta a una certa quota. Io credo che anche lungo un percorso perlopiù orizzontale serva un tempo simile. Un trekking lungo, anche solo un centinaio di chilometri, non si svela tutto subito, richiede pazienza e anche un po’ di dolore, non soltanto quello del corpo. Ti insegna davvero che cos’è un chilometro e cosa significa “mettere un piede davanti all’altro”. E poi andare avanti, percorrere quello successivo e quello dopo ancora. Tutto perché muoversi lentamente, a passo d’uomo, è un modo a cui siamo molto meno avvezzi nel mondo moderno, dove i chilometri riusciamo a consumarli a velocità incredibili rispetto a un secolo fa.

Un trekking di questo tipo mi ha dato anche l’occasione di mettere in pausa tutto ciò che non aveva direttamente a che fare con il trekking. Sarà un’ovvietà applicabile a qualunque vacanza, ma la mia esperienza dei sette giorni di cammino è stata davvero totalizzante, e non si è trattato solo di non avere (quasi) mai una connessione a internet per comunicare come siamo abituati oggi.

E poi ci sono le persone che puoi avere il tempo e l’occasione di conoscere durante un trekking del genere, a cominciare da quelle con cui decidi di pianificare il percorso. Sono fortunato a conoscere Federico, ormai compagno fisso di diverse avventure in montagna. So già che con lui c’è la sintonia ideale per questo tipo di vacanza, dove la soddisfazione è la fatica che devi metterci per portare a casa tutti i chilometri della tappa. Grazie Fede per aver scelto di organizzare e condividere anche questo trekking!

Sono preziosi anche gli incontri fortuiti con persone sconosciute che camminano lungo percorsi diversi dal tuo e con altre mete. Dalla bidella trentina a cui piace camminare in solitaria agli studenti di geologia in giro per i campionamenti; dagli scout con uno zaino da venticinque chili a quelli che fanno trail running e viaggiano ultraleggeri. La vita del rifugio, poi, nel condividere la cena con persone che non hai mai visto o raccontarsi la giornata davanti a una grappa prima che il bar chiuda, ti convince che forse siamo tutti lì per lo stesso scopo.

Anche se non abbiamo più da raccontare Cosa ci aspetta domani1, possiamo già anticipare quali sono i progetti in cantiere, o perlomeno quelli a cui abbiamo pensato o stiamo considerando da un po’ – anche a costo di mescolare una buona dose di sogni.

-

Ci sono almeno altre due sezioni del Sentiero Italia che ci incuriosiscono parecchio: quella tra Piemonte e Val d’Aosta e quella che dal Piemonte porta in Lombardia, più o meno dove l’anno scorso abbiamo cominciato l’Alta Via dell’Adamello.

-

Quest’anno sul Sentiero Italia abbiamo attraversato una varietà incredibile di ambienti montani, boschivi, rocciosi. Ma quello che ci è rimasto più nel cuore è il selvaggio Lagorai. Abbiamo scoperto che esiste la Translagorai, 5 giorni e poco meno di 80 chilometri immersi in questo ambiente quasi incontaminato, e non poteva che entrare di diritto nella lista Dove vorremmo andare prossimamente? L’idea che ci stuzzica di più è fare questo percorso in autonomia, ossia in tenda e bivacchi.

-

Per ultima – ma solo perché, per adesso, si tratta di un’idea di progetto escursionistico che richiederà preparazione e allenamento (il problema al ginocchio mi ha insegnato qualcosa) – l’intenzione più ambiziosa di tutte: percorrere un tratto del Pacific Crest Trail, un lunghissimo2 trekking scenico che segue l’intera costa ovest degli Stati Uniti, dal Messico al Canada attraversando California, Oregon, e Washington. L’intero percorso è davvero un’impresa titanica non da poco, ma già progettare e riuscire a realizzare un paio di mesi di cammino su quel percorso è indubbiamente tra i miei3 sogni di long distance hiker.

-

Anche perché stiamo scrivendo questa pagina ben tre settimane dopo la conclusione del trekking. ↩︎

-

Senza alcun intento di stilare una classifica, il Pacific Crest Trail si sviluppa per un totale di 4270 km, sfiorando i 4000 metri di quota nel punto più alto. L’intero Sentiero Italia CAI copre ben 6170 km. ↩︎

-

Ho soltanto sondato l’interesse di Federico a questo progetto. Non si è sbilanciato, ma mi pare che l’idea l’abbia incuriosito quanto basta. ↩︎

Giorno Sette: la Regina che era bianca

| Dettagli tappa | |

|---|---|

| Partenza | Rifugio Contrin, 2012 m |

| Arrivo | Arabba, 1645 m |

| Tappe intermedie | Rifugio Castiglioni, 2045 m; Rifugio Padon, 2407 m |

| Lunghezza | 20.7 km |

| Dislivello | +908/-1283 m |

La Cresta del Padon appartiene geograficamente al gruppo della Marmolada, anche se si discosta sia morfologicamente che cromaticamente dal resto del complesso montuoso. Qui, infatti, non dominano chiari calcari bensì scure rocce vulcaniche che fungono da fertile terreno per smeraldine praterie d’alta quota. L’ultima tappa della variante trentina si presenta non troppo faticosa, con una salita molto frequentata e una seguente discesa che sorprendentemente sa regalare degli attimi di intimità davvero impensabili al cospetto di impianti e piste da sci. Il punto di forza di questo percorso è indubbiamente quello panoramico, con lo sguardo che difficilmente riesce a scostarsi dal bianco velo della “regina” Marmolada prima e dal castello roccioso del Sella poi.

L’ultima tappa di questa nostra traversata trentina è ancora una modifica del percorso originale del Sentiero Italia: combineremo la tappa di collegamento che dal Rifugio Contrin porta al Rifugio Castiglioni con quella che taglia il versante opposto alla parete settentrionale della Marmolada, un vero e proprio belvedere sulla Regina delle Dolomiti.

Dopo una notte abbastanza ristoratrice e tranquilla – nonostante fossimo in una camerata da nove – quando arriviamo in sala da pranzo alle 7 e 30 la troviamo già piena; perciò dividiamo il tavolo con due ragazze canadesi1 che sono venute da Calgary, in Alberta, per farsi un giro sulle nostre Dolomiti: stanno percorrendo il nostro stesso percorso in senso inverso, dirette a Passo Rolle passando per Passo Valles. Sono rimasto davvero stupito dalla loro scelta, ma è pur vero che le Dolomiti sono patrimonio UNESCO e sono mete parecchio celebri oltre i confini italiani – in fondo, non è molto diverso dalla scelta di un europeo di andare a fare trekking sulle Ande cilene o la Sierra Nevada in California.

Dopo colazione, salutiamo le due ragazze al momento di chiudere gli zaini, e alle 8:31 siamo già sul sentiero 602 che scende attraversando la Val Contrin – altra valle totalmente votata all’alpeggio – fino al piccolo abitato di Alba, frazione di Canazei, ultimo paese della Val di Fassa. Il sentiero è in realtà una strada carrozzabile che permette di raggiungere il rifugio in fuoristrada (il permesso è riservato alle attività del rifugio), perciò riusciamo a fare un paio di scorciatoie per abbreviare la discesa, anziché seguire tutti i tornanti.

Prendiamo una deviazione quando siamo ormai a quota 1500 metri e ci dirigiamo verso Penìa, altra piccola frazione di Canazei. Da qui, il Sentiero Italia comincia a risalire il torrente Avisio, corso d’acqua d’importanza geologica notevole avendo scavato la Val di Fassa, la Val di Fiemme, e la Val Cembra prima di buttarsi nell’Adige. Sul sentiero che lo costeggia e che riprende lentamente quota, ci sono numerosi pannelli illustrativi che spiegano la storia dei paesi che sono nati intorno al torrente, dei ritmi stagionali che lo caratterizzano, nonché la flora e la fauna che lo popolano. È un tratto abbastanza riposante2 della doppia tappa di oggi.

Il sentiero attraversa un paio di volte e affianca per alcuni chilometri la strada statale in direzione del lago di Fedaia (e l’omonimo passo); poi si discosta definitivamente e rimane più in basso, attraversa lo spazio aperto di un pianoro chiamato Pian Trevisan, e raggiunge l’inizio del sentiero 605 nei pressi di un hotel alpino. Qui si comincia a fare sul serio perché il sentiero s’inerpica subito fra sassi e alti gradoni rocciosi, spianandosi dopo circa cento metri di dislivello. La salita riprende più dolce e graduale, in un ambiente boschivo perfetto per l’ennesima giornata molto calda, fino a raggiungere il Col Ciampè (circa 1850 m). Da qui, ormai al limite del bosco, percorriamo un ultimo tratto ripido che ci porta proprio sotto allo sbarramento della diga del lago di Fedaia vicino alla quale si trova il rifugio Castiglioni Marmolada. Siamo già ben oltre l’ora di pranzo, perciò ci concediamo una pausa più lunga e un pasto veloce al rifugio (gnocchetti al ragù di cinghiale e carne salada trentina).

Dopo pranzo, Federico si sente obbligato a fare un pit stop al lago artificiale per provare a recuperare il tono muscolare di gambe e piedi – entrambi ci hanno portato per più di 90 chilometri dalla Val di Fiemme – e anch’io provo a cercare un po’ di sollievo al ginocchio acciaccato.

Decidiamo di modificare anche la tappa del pomeriggio per fare meno dislivello in salita: taglieremo il pezzo di sentiero che passa per il rifugio Luigi Gorza – altro autogrill invernale delle piste che scendono da Porta Vescovo – e andremo direttamente al rifugio Padon, prendendo una traccia di sentiero che sarà un po’ da inventare nel primo tratto.

Il primo pezzo della variante è giusto segnato nel punto in cui devia dal sentiero principale che porta al rifugio Gorza. Abbiamo però la mappa digitale, il GPS, e sappiamo in che direzione dobbiamo andare. Dobbiamo soltanto seguire la traccia a mezza costa – chiaramente un terreno battuto da capre e pecore – e prendere quota fino a circa 2400 metri. Incontriamo un paio di persone che hanno deciso di fare la stessa deviazione al contrario, e ciò ci convince di essere sul percorso giusto, anche se in alcuni punti l’unica traccia è solamente l’erba calpestata da chi è passato prima. In cambio, però, abbiamo la fortuna di poter ammirare il versante nord della Marmolada in tutta la sua vastità.

È impossibile non notare due cose. Si riesce a distinguere3 il punto in cui si è creata l’enorme voragine in seguito al distacco di inizio luglio: assomiglia molto all’ingresso di una caverna, ma si capisce che la geometria originale di quella parte di ghiacciaio è stata profondamente modificata da un evento improvviso. È anche innegabile la condizione pietosa del ghiacciaio: la seconda foto mostra chiaramente una lingua del ghiacciaio coperta con teli bianchi nella speranza di poterla salvare.

Due numeri, così per dare un’idea dello stato attuale:

Le ultime indagini sullo spessore del ghiaccio con georadar rivelano come l’intero bacino abbia ormai perso l'80% del proprio volume, passando dai 95 milioni di metri cubi nel 1954 ai 4 milioni attuali4.

Alcune ottimistiche previsioni sperano di mantenere il ghiacciaio per i prossimi 30 anni. Osservandolo dal vivo per la prima volta, noi due ci siamo detti che sarà già tanto se la parte più alta resisterà per altri 15 anni.

Attraversiamo (letteralmente) un gregge di pecore che si muove verso prati più alti e, dopo essere ritornati su sentiero ben segnato – quello che avremmo percorso se fossimo saliti fino al rifugio Gorza – arriviamo al Passo del Padon in cui converge l’omonima cresta e su cui si sviluppa una famosa ferrata nota come Sentiero delle trincee. Qui si nota subito come le rocce siano di tutt’altra specie rispetto alle Dolomiti: si tratta di scure rocce vulcaniche che hanno favorito la crescita delle praterie in quota, adesso colonizzate da greggi di pecore. Mentre dal passo ci avviciniamo all’ultimo rifugio lungo un sentiero pianeggiante, notiamo anche dei massi conglomerati, abbastanza diffusi in questa zona: si tratta di rocce composte da una matrice di origine dolomitica e dal materiale di sgretolamento degli antichissimi edifici vulcanici che si trovavano in Val di Fassa. Pur non avendo la minima competenza in materia, è difficile non prestare attenzione alle “opere” di questo museo geologico a cielo aperto, che espone quasi 250 milioni di storia della Terra.

Al rifugio Padon la stanchezza si fa sentire parecchio. Beviamo due bevande zuccherate e mangiamo l’ultima barretta, ma sappiamo che l’energia necessaria l’attingeremo soltanto dalla certezza che la discesa verso Arabba sarà davvero l’ultima.

Alle tre ci rimettiamo in spalla gli zaini e cominciamo la discesa che sarà prevalentemente lungo piste da sci di Arabba, parte dell’enorme comprensorio del Sellaronda. Dopo un primo pezzo molto ripido che percorre una stretta traccia scomoda su ghiaia, camminiamo quasi in piano fino alla stazione intermedia della funivia, che da Arabba sale alla forcella Porta Vescovo. Inutile dire quanto siamo tentati di prendere la seconda funivia in discesa per risparmiare un po’ le gambe. Alla fine, però, ci ripetiamo il mantra che ha segnato questo trekking sin dall’inizio – “bisogna solo mettere un piede davanti all’altro” – e continuiamo la discesa. Usciamo dalla pista da sci percorrendo un pezzo del Sentiero Geologico di Arabba, e anche questo sentiero non ci fa sconti sulla pendenza. L’unico pregio del seguire lo sviluppo di una pista da sci è che sei sicuro di percorrere la via più breve: arriverai a destinazione senza troppe varianti di percorso, ma probabilmente anche senza più le gambe.

Alle 17:32 arriviamo alla stazione di partenza della funivia di Arabba e, prima di orientarci e capire dove sia il nostro ultimo alloggio, ci stringiamo la mano come abbiamo fatto tante altre volte arrivati in cima a una vetta o al termine di una via d’arrampicata: la variante trentina, quella storica5, del Sentiero Italia l’abbiamo ufficialmente conclusa6 🙌 🏔️

-

Edoardo si prende il merito di aver iniziato il discorso avendo notato che una di loro indossava una bandana del Banff National Park, un’area di wilderness di più di seimila chilometri quadrati, all’incirca quanto l’intera provincia di Trento, giusto per mettere le cose in prospettiva. Il parco nazionale fa parte di un’area anch’essa considerata UNESCO World Heritage. ↩︎

-

“Riposante” per modo di dire, visto che già ieri Edoardo si è ritrovato un ginocchio abbastanza dolorante, soprattutto in discesa, forse a causa un piccolo problema ai legamenti. È evidente che non era abbastanza allenato per un trekking del genere. ↩︎

-

La foto in questa pagina è troppo piccola. Si può sempre cliccarci sopra per aprirla nelle dimensioni originali e ingrandirla un po’, nonostante la qualità sia un po’ scarsa: non è stata scattata con un teleobiettivo particolare. ↩︎

-

Dalla scheda a pag. 156 del volume 11 della collana Sentiero Italia CAI. ↩︎

-

La seconda variante, più recente, del Sentiero Italia è quella altoatesina: dal Rifugio Potzmauer arriva sempre ad Arabba lungo un percorso più a nord e lungo il quale si passa dal Latemar, il Catinaccio, il lago di Carezza, l’Alpe di Tires e di Siusi, fino a Selva Val Gardena, Puez, e infine il gruppo del Sella. ↩︎

-

A voler essere precisi, non abbiamo percorso la prima tappa della variante trentina, quella che va dal Rifugio Potzmauer a Molina di Fiemme. ↩︎

Giorno Sei: ambiente lunare sui Monti Pallidi

| Dettagli tappa | |

|---|---|

| Partenza | Passo Valles, 2030 m |

| Tappe intermedie | Passo S. Pellegrino, 1899 m |

| Arrivo | Rifugio Contrin, 2012 m |

| Lunghezza | 17.6 km |

| Dislivello | +1260/-668 m |

Tappa di media lunghezza dal buon dislivello che porta alla scoperta del versante meridionale del gruppo della Marmolada, caratterizzato da superbe cime rocciose e sicuramente meno celebrato di quello settentrionale che ospita il più esteso ghiacciaio dolomitico. Dalle bucoliche distese pascolive del Fuciade si raggiungono le alte zone rocciose del Passo delle Cirelle, passando prima per ampie praterie d’alta quota e importanti ghiaioni. Lo spettacolo non manca di sicuro, sia per la bellezza degli ambienti su cui ci si muove, sia per la vista sui numerosi gruppi montuosi che riempiono via via l’orizzonte. La vista sulla leggendaria Parete Sud della Marmolada, teatro di epiche ascensioni, è di quelle che difficilmente si possono dimenticare.

Il primo tratto di questa sesta giornata di cammino è stato il pezzo mancante di ieri, ossia la congiunzione del Passo Valles con il Passo S. Pellegrino. Il percorso era piuttosto semplice e abbastanza lineare dovendo collegare due passi alla stessa quota, però la guida ci aveva avvisato che la traccia non sarebbe stata sempre visibile, in mezzo a comprensori sciistici e incroci con altri sentieri. È bastato poco perché sbagliassimo direzione – avremmo potuto guardare un po’ più spesso la traccia GPS, ma il nostro passo era già spedito. Così ci siamo trovati in meno di due ore su al Col Margherita, a 2500 metri, il punto più alto del comprensorio del S. Pellegrino.

L’errore ci sarebbe costato più di due ore se, ironia della sorte, non ci fosse stata la possibilità di prendere la funivia in discesa. Non abbiamo avuta molta scelta, ci mancavano troppi chilometri e dislivello per voler fare gli integralisti.

In cinque minuti, la funivia ci porta al San Pellegrino dove ci rendiamo subito conto che è un sabato di metà luglio. Sulla strada, tutta carrozzabile, che porta alla bucolica conca di Fuciade sembra di essere lungo un pellegrinaggio. In meno di venti minuti, su un comodo falsopiano raggiungiamo il Rifugio Fuciade1, una stupenda costruzione in legno in pieno stile trentino (sauna inclusa). L’avevamo pure considerata come un potenziale punto di appoggio, ma il listino prezzi per una notte con colazione ci ha subito dissuaso, senza contare l’affollamento turistico di questa zona – che però se lo merita tutta: i pascoli curatissimi che incorniciano alcune vette del gruppo della Marmolada da un lato e i profili delle Pale di San Martino dall’altro.

Da qui partirà il nostro sentiero (n. 607) che diventerà l’escursione vera e propria della tappa giornaliera. Cogliamo quindi l’occasione per mangiare un panino (l’inflazione della zona da vip si fa sentire) e poi, ben incremati, ripartiamo con destinazione intermedia il Pas de le Cirele. Saliamo con una pendenza graduale sempre tra i prati da pascolo, puntando alle vette minori del gruppo della Marmolada: la Punta Jigolé, l’Ombretola, e il Sasso di Valfredda. Dopo quasi un’ora, il sentiero si fa un po’ più ripido e i tornanti aumentano finché raggiungiamo un pianoro, il Busc da la Tascia, sotto l’omonima vetta (Sas da la Tascia). Qui incontriamo una coppia che si sta prendendo una pausa dopo aver concatenato un paio di vette, l’Ombreta (3011 m) e la sorella minore Ombretola (2930 m); quando gli raccontiamo del nostro percorso, anche loro ci fanno i complimenti per avere già quasi cento chilometri nelle gambe. Più tardi al rifugio, ci siamo chiesti come mai parlare del Sentiero Italia susciti un’ammirazione del genere in questa regione, visto che di percorsi impegnativi e lunghi ce ne sono in abbondanza. Però fa senz’altro piacere che qualcuno riconosca la nostra piccola impresa.

Pochi passi oltre il Busc il terreno diventa un tipico ghiaione, da cui ci si accorge di come questo punto era la soglia di un ghiacciaio ormai scomparso. Nonostante la traccia del sentiero sia ben visibile e salga comodamente la fiumana di ghiaie in cui ci troviamo, tra la pendenza e il sole del primo pomeriggio smettiamo di chiacchierare perché entrambi dobbiamo trovare il passo adatto a salire senza strappi.

Incontriamo solo poche persone che scendono – Cristina, la nostra prima conoscenza alla Malga Consèria, ci aveva avvisati che è talmente divertente percorrere questo ghiaione in discesa che quasi nessuno lo fa in salita – e, ormai al passo, abbiamo la fortuna di incrociare un camoscio: in meno di un minuto risale di corsa il versante opposto al passo, scavalca la cresta, e si butta a capofitto nel ghiaione dove noi abbiamo appena sudato per una buona ora e mezzo. Non c’è modo di riuscire a fare una foto o un video, perciò ci limitiamo a guardarlo e riconoscere che questa è casa sua, siamo noi gli estranei.

Scendiamo verso nord sul versante opposto, ancora tra ghiaie e roccette, su un sentiero un po’ meno faticoso del ghiaione. In pochi minuti, raggiungiamo un pulpito roccioso con un monumento ai caduti della Grande Guerra e uno splendido panorama sul Sassolungo.

Scendiamo rapidamente nella Val de le Cirele, verso i prati del Passo San Nicolò. Il terreno cambia di nuovo, alcuni abeti e un manto erboso sostituiscono roccia e ghiaia. Questo tratto del Sentiero è quello in cui abbiamo incontrato più animali: oltre alla cavalcata del camoscio e uno stambecco appostato su un cucuzzolo roccioso – impossibile fargli una foto senza un obiettivo adeguato – avremo intravisto almeno una decina di marmotte che uscivano dalle tane, correvano sui prati, e rientravano altrove dopo averci osservato per un po’ a distanza di sicurezza. Capiamo di essere ormai vicini alla meta quando attraversiamo alcuni pascoli e i loro abitanti, e pochi minuti dopo raggiungiamo la Malga Contrin (2027 m), in cui si possono acquistare diversi prodotti caseari. Il rifugio Contrin2 è proprio dietro l’angolo.

-

Non abbiamo foto, ma fatevi un giro sulla pagina web del “rifugio” per capire di che zona idilliaca si tratti. E per dare un’occhiata ai prezzi, se volete. Evitate il weekend, se possibile. ↩︎

-

Anche noto come “il rifugio degli Alpini” perché nel 1921, dopo averlo ricostruito una volta terminata la guerra, la SAT lo donò all’Associazione Nazionale Alpini. Si vede che è un rifugio attrezzato per ospitare almeno duecento coperti e forse un centinaio di posti letto, distribuiti in due edifici separati. ↩︎

Giorno Cinque: il richiamo del Mulaz

| Dettagli tappa | |

|---|---|